The Purpose of Something Is What It Does

(Why business doesn’t work the way we think it does)

When we design a new system—whether it’s a piece of software, a customer process, or a new way of working—we start with a clear idea of what it’s supposed to do.

But that’s not its purpose.

In systems theory, the purpose of a system is what it actually does—not what the designer intended, not what the users hoped, and definitely not what the PowerPoint said.

If a system constantly fails to do what it was meant to do, then that’s not its purpose. Its real purpose is failure.

This might sound abstract, but it’s not. This explains why businesses struggle to deliver change, why strategies collapse in execution, and why control is always just a little out of reach.

How Business Change Actually Works

Here’s what goes into any significant business change:

Problem definition

Requirements analysis

Architecture, design, development

Testing, deployment, operation

And everything in between, across time and different organizations

Now add:

People leaving and joining

Shifting goals

New regulations

Technology updates

Supplier problems

Miscommunications

This is not a machine. This is a living, changing, interacting system.

And in such a system, no manager, however brilliant, can see or control everything that matters.

Why Control Fails (and Feedback Saves Us)

Managers are taught to believe they can direct change. We give them dashboards, Gantt charts, and performance tools. But the truth is: the control system never has enough reach or awareness to match the complexity of the system it’s trying to manage.

In systems theory, this is called requisite variety—you can’t control a system unless your ability to act is as varied as the system itself. That’s almost never the case in business.

What saves us—what actually keeps systems going—is informal feedback:

A frontline worker who spots an issue and fixes it before anyone notices

A customer workaround that reveals the real use of a product

A middle manager who patches the gap between two misaligned departments

A team that quietly ignores the unworkable bit of the official process and gets the job done anyway

These things don’t show up in formal reports. But they’re what hold everything together.

The Invisible System That Works

We act as though the official structure—the boxes and arrows—is the real system.

But what actually works is often the shadow system: the network of informal feedback, tacit knowledge, side-channel fixes, and shared understanding.

The irony is that most management effort goes into optimizing the formal system. But that system doesn’t have the variety to respond to real-world complexity. It can’t adapt quickly. It can’t learn in time.

So most “control” is an illusion. And most successful action is really alignment with what’s already happening.

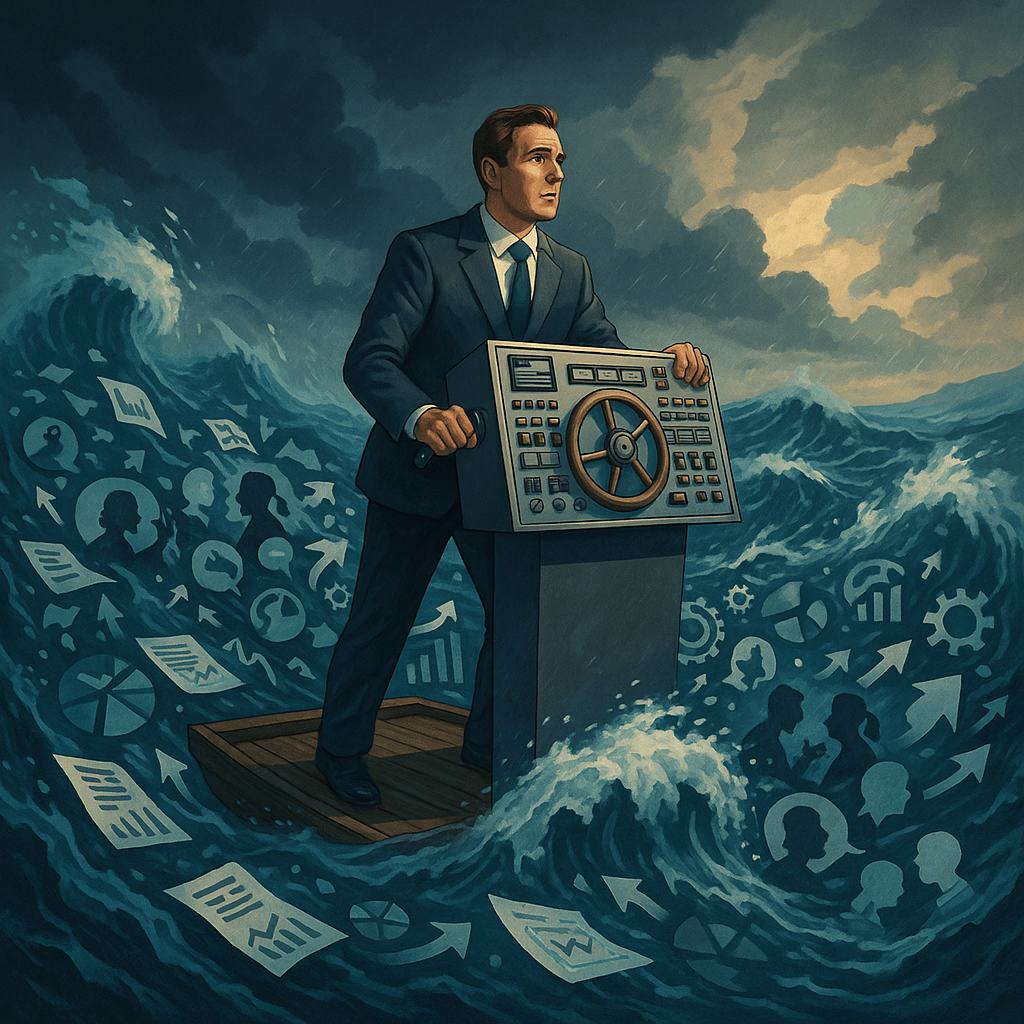

The Manager as Surfer, Not Engineer

If you accept this, the manager’s role changes.

You’re not driving a train on fixed tracks. You’re riding waves in an unpredictable ocean. You can’t control the water—but you can learn to sense its movement, position yourself well, and steer with timing and humility.

That doesn’t mean giving up on structure. It means recognizing where structure helps and where it gets in the way.

The best managers know: you don’t impose order—you discover it. You don’t force control—you create space for the right patterns to emerge.

Final Thought

Business doesn’t work the way we think it does. It works because of the things we often ignore: informal feedback, tacit knowledge, adaptive behavior.

If you want to lead real change, stop pretending the map is the territory.

And stop believing that you’re in charge of the ocean.